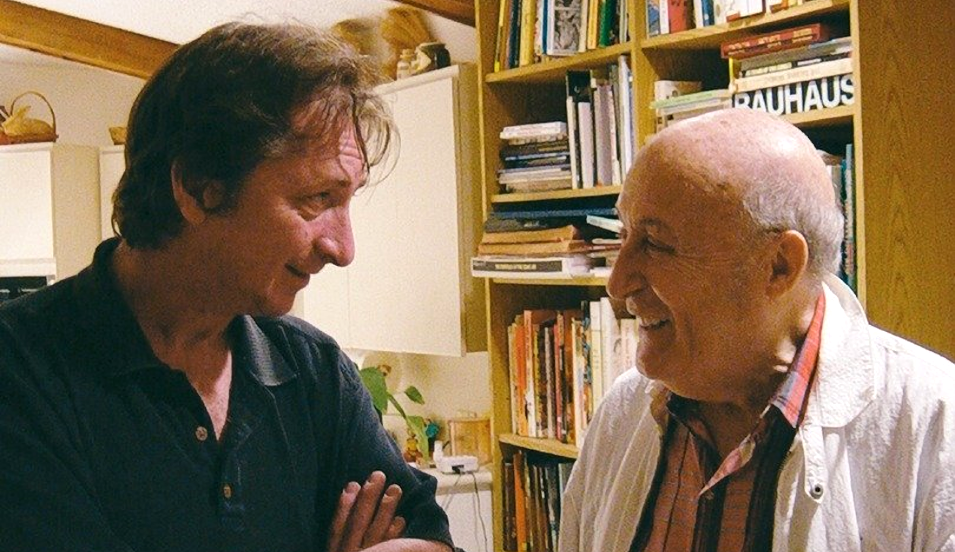

I’ve had a little-worn copy of Eisner/Miller on my shelf for years. Published in 2005 by Dark Horse Comics, and to my knowledge never reprinted, it offers a dialogue between two respected cartoonists in the mold of François Truffaut’s celebrated conversations with Alfred Hitchcock. In this case, the pairing is of Will Eisner (best known for The Spirit) and Frank Miller (of Dark Knight Returns and Sin City fame).

I’ve had a little-worn copy of Eisner/Miller on my shelf for years. Published in 2005 by Dark Horse Comics, and to my knowledge never reprinted, it offers a dialogue between two respected cartoonists in the mold of François Truffaut’s celebrated conversations with Alfred Hitchcock. In this case, the pairing is of Will Eisner (best known for The Spirit) and Frank Miller (of Dark Knight Returns and Sin City fame).

I’d only read the book once since I bought it, 15 years ago. Considering later developments in both men’s lives, and in the American comic book business in general, I thought it deserved a second look.

Having read it a second time now, I admit I remain perplexed. I just can’t see these men as peers, let alone genuine friends. Colleagues? Certainly. But their worldviews and their motivations seem to differ so widely that it’s hard to imagine they would have much to talk about outside of a contrived situation like this extended interview.

Truffaut wrote in his preface to the revised edition of Hitchcock/Truffaut, “In examining his films, it was obvious that [Hitchcock] had given more thought to the potential of his art than any of his colleagues.” Truffaut himself probably deserved similar praise, since the book was his brainchild and the conversation was largely driven by his own thoughts. Between Eisner and Miller, however, it becomes clear that only one of the two deserves much credit for insight.

Creators from two different worlds

On one hand, we have Eisner. He cut his teeth in the early days of the comics industry, forging a lucrative partnership with Jerry Iger to produce adventure strips for various publishers and newspapers. He enjoyed further success with his own character, the Spirit, and by packaging instructional comics for the U.S. Army and private businesses such as General Motors. In the 1970s he pioneered the long-form graphic novel format with his seminal work, A Contract with God, and the series of books that followed.

A child of the Great Depression, Eisner was ever the pragmatist. Throughout most of his career, he was not only an artist but also an employer of other talent. As he says in his talk with Miller, “I feel a bit like Horatio Alger. I worked hard. I didn’t marry the boss’s daughter, but I worked hard, kept my nose clean, did the right thing, saved my money, and ultimately wound up being the chairman of the board.”

Miller, on the other hand, admits to no such mercantile values. Where Eisner says he “loves business,” Miller repeatedly speaks of comics as an “outlaw” medium, one that has suffered from lack of respect and being yoked to crass commercialism since its inception. As he tactlessly observes, “When I first came in, during the late seventies, there was this constant sense that we were the ‘niggers’ of entertainment – and I think that persists and hasn’t progressed.”

Miller waxes on about wanting to dispel the atmosphere of “cowardice and shame” that he sees as pervading the comics business. “The sickness is self-contempt,” he says. “I am the young puppy of a certain generation that started becoming a force in comics in the seventies and eighties, but I still see the industry of comics hobbled by this sense of worthlessness that thinks of the medium as a genre that’ll be shaken off over time. It still amazes me how deep-rooted that is.”

Eisner stresses the importance of comics as a medium and not merely a business venture, yet while Miller scoffs at the influence of publishers, Eisner acknowledges their importance. Miller grumbles about comics creators getting “screwed,” but Eisner says, “Don’t expect from publishers something that they cannot give or have no intention of giving … whether publishers are interested in art or not, publishers are to be respected. They’re the guys who understand marketing.”

The two even differ on comics as a form. Miller explains that in a world inundated by such media as television, movies, and the internet, his use of staccato imagery in comics such as The Dark Knight Returns is “trying to imitate channel surfing.” Eisner, conversely, insists that he has “no intention of capturing the essence of any other medium.”

More pontification than debate

You might think this dichotomy would lead to some heated exchanges. You’d be disappointed. In his introduction, Miller says, “Will Eisner and I argued a lot,” but you don’t get much of that in the book itself. It’s more just Eisner being patient with the younger man.

As a long-form interview, Eisner/Miller is meandering, lacking the structure that Truffaut brought to his 50-hour-long dialogue with Hitchcock (and whatever edits were made afterward). It seems clear that the talks between the two cartoonists took place over a single day, bouncing from location to location in Eisner’s adopted home of Florida. The result is an extended chat that lacks both the precision and the insight of the best interviews in, say, The Comics Journal.

What’s more, unlike Hitchcock/Truffaut, Eisner/Miller can’t be described as a book about creativity or the process of art, either. Little is mentioned about individual projects, the decisions made, or why – except, perhaps, when it serves to highlight the difference once again between Eisner’s mentality and Miller’s.

Eisner’s comments reveal him as a deep thinker, a careful craftsman, and a sensitive chronicler of his times. He aims to reach new readers and to introduce them to new ideas through the medium of comics. He explains his approach to the semi-autobiographical comics of his later life as “being a reporter.” Elsewhere he describes his then-current work in progress, Fagin the Jew, as “a polemic more than entertainment.”

Miller lays claim to similar motives, yet a survey of his work reveals a creator fixated on entertainment, and of a puerile kind. His men are brawny, tough, and of few words. His women are Madonnas or whores, but neither role takes up so much of their time that they can’t also be ninja assassins. He boasts of the humor in one of his comics, Sin City: Family Values, saying, “There’s a running gag in it where our hero is hit by a car, and he flies through the air and lands, and these mafioso types come to pick him up because he’s arranged for it.” In one instance, he says, the gag goes on for four pages of illustration before the character hits the ground.

That bit could be brilliant in the right hands. The Simpsons got plenty of mileage out of Sideshow Bob stepping on a rake. But Miller seems to think his car-crash slapstick demonstrates the work of a sophisticated auteur lobbing truth-bombs at the dullards in the corporate boardroom. Someone needs to remind him that although the deeper meaning of Citizen Kane might be lost on some audiences, nobody even looks for it in The Fast and the Furious.

15 years on

For what it’s worth, Eisner does speak of the promise he sees in Miller. As he charitably observes, “You’ve evolved. The only reason I’m spending time with you is because no matter what I say and how insulting I am, still I regard you as an involving [sic], growing person.” Unfortunately, Miller’s continued evolution has not all been in a positive direction.

Eisner died on January 3, 2005, from complications related to heart surgery. He would not live to see his book-length talk with Miller published.

In the years since, Miller has suffered his share of setbacks. Rumors of health problems have dogged him, including not just undisclosed illness but also an alleged struggle with substance abuse that reportedly strained his relationships, both personal and professional.

His work has likewise suffered – and I say this as one who likes a lot of Miller’s stuff. Personally, I think his masterwork remains Ronin, his mishmash of European-style dystopian sci-fi à la Métal Hurlant with Japanese samurai manga. It’s far from perfect, but it shows a creative firebrand at the top of his powers, given a budget and carte blanche to put pen to paper any way he chose, for the first time. The Dark Knight Returns is a brilliantly executed takedown of superhero comics and 1980s media tropes. I also really enjoy Miller’s collaborations with David Mazzucchelli (Batman: Year One, Daredevil) and Geoff Darrow (Hard Boiled). But I think Sin City ran out of steam after the first couple of stories, and it all went downhill from there.

The fall of Frank Miller

So, what happened? By the time Eisner/Miller was published, Miller had already produced The Dark Knight Strikes Again, a garish – dare I say, ugly – hodgepodge of DC superheroics that was received by readers with an awkward mix of cautious approval, puzzlement, and outright rejection. Next came All-Star Batman and Robin, a hallucinatory, much-derided take on the characters that’s best known for the Caped Crusader’s bizarre behavior and the cringe-inducing phrase, “I’m the goddamn Batman.”

But the true nadir of Miller’s comics output was Holy Terror. Miller made mention of it in Eisner/Miller as a project he conceived in reaction to the events of September 11, 2001. But while it was proposed as another Batman project, it was ultimately rejected by DC’s editors and was eventually published as the first hardcover release by Legendary Comics in 2011.

It’s easy to see why DC passed. Miller had already demonstrated his mounting xenophobia and subtle racism in 3oo, in which he depicted Persians – whose descendants are the people of modern-day Iran – as grotesque, diabolical subhumans with mutant-like bodies and a proclivity for self-mutilation. In the published version of Holy Terror, which featured thinly veiled versions of Batman characters, he declared all-out war on Islam in a way that only an angry man who spends all day hunched over a drawing table could. Nail bombs exploded, innocents died, and terrorists got their bloody comeuppance.

Miller followed up Holy Terror with a rant on his personal blog accusing Occupy Wall Street protesters of being un-American and urging them all to stop wasting their time undermining the country and instead go to war and die fighting the Muslim enemy – as he presumably would have done himself, if he didn’t have comics to draw. One can almost picture Miller standing with one foot on his coffee table, brandishing a watercolor brush in one hand and with a towel wrapped around his shoulders for a cape, shouting victory speeches into the mirror. (Miller later apologized for this post, attributing it to a “dark time” in his life.)

Miller has returned to comics a few times since this embarrassing period. First, he pushed out Dark Knight III: The Master Race, a pastiche of his earlier work, this time featuring art by Andy Kubert and Klaus Janson. Later, he did a sequel to 300. Neither offered much of interest.

But honestly, who needs comics when Hollywood beckons? In Eisner/Miller, Miller says he’s “turned down a lot of offers” to bring Sin City to the big screen. He was being coy, of course; Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City movie was released in late 2005, the same year that the book was published, with Miller granted a co-director credit. Though the film was a modest success, a 2014 sequel flopped. In between the two, Miller made his solo directorial debut with The Spirit, a purported adaptation of Eisner’s celebrated character that had so little in common with its source material and was so thoroughly execrable in its execution that Eisner must surely be revolving in his grave.

Yet who can blame Miller for following where the comics business leads him? There’s no denying that today’s big-budget comic book adaptations are more profitable than DC’s and Marvel’s publishing businesses combined. As Miller tells Eisner, “If you’re gonna sell your tail on the street, at least get some good money for it.”

Whither the comics business?

“Good money” is precisely what’s not to be had in comics publishing, owing largely to the mainstream medium’s refusal to evolve past its Depression-era roots. Eisner and Miller both lament the persistence of the 32-page pamphlet format of monthly comics, which originated in the 1930s. As Eisner observed in 2005, “A 32-page book is now $2.25 – who’s going to pay that much for it?”

He goes on to note that it’s not just the publishers but the entire structure of the business that’s to blame. In a world in which a single company handles at least 90 percent of distribution to specialty comics retailers, publishers have little choice in how they sell their comics in the modern market, just as retailers have little choice in how to stock them in their stores. “If Steve Geppi [President of Diamond Comics Distributors, Inc.] offers to buy your books only at sixty percent off, period,” Eisner observes, “then you’ve got no place else to go. There is nobody else.”

Both men see hope in alternative markets, particularly mainstream bookstores. And it’s true; bookstores have since done well for trade paperbacks and especially manga (with the collapse of the Borders Books chain being a notable setback). Nether Eisner or Miller sees traditional comics shops going away, however – and why should they? Fifteen years ago, there was no way they could have predicted Covid-19.

The global pandemic has had a massive impact on every segment of the economy. Retail has been particularly hard-hit, with most stores being ordered to shut their doors for months. The paper-thin margins of the comics business leave many retailers struggling to make rent even in an ordinary year. It’s likely that this year’s setbacks will be too dire for many stores to recover from.

It’s doubtful that even the publishers will emerge unscathed. On March 31, 2020, Diamond Distributors’ Steve Geppi announced that the company would not be able to pay its bills for comics it had already ordered. DC and Marvel followed suit by issuing “pencils down” instructions to its creators and postponing the ship dates for issues already produced. Even if retailers were able to open their doors, they would have no product to stock on their shelves.

Cool stories, bros

As of this writing, the future still looks grim for the comics business. No, we certainly haven’t seen the last movies and TV shows based on DC and Marvel characters. But where the actual act of putting pen to paper (or graphics tablet) and making comics goes from here is anyone’s guess – let alone how to sell them. In the absence of brick and mortar retailers, digital comics might offer a workable alternative, but the aging mainstream fan base has been reluctant to throw much money that way so far. It seems likely that so-called alternative comics creators will become a more dominant force in tomorrow’s comics business, leading the way forward with various combinations of crowd funding, digital delivery, print on demand, social media marketing, and other 21st century tools.

That being said, although the discussion in Eisner/Miller was intended to address the comics business both “in the now” and for the future, a contemporary reading reveals it to be mainly a historical artifact. Miller’s remembrances of breaking into comics in the 1980s have no more relevance to what future comics creators can expect than do Eisner’s accounts of the business in the postwar era. Rather than an instructional treatise for would-be comics creators, then, Eisner/Miller is best viewed as a kind of time capsule, one that offers a snapshot of the comics business that was and of two great creators of yesteryear.

Thanks, an excellent article. My question is: How do we introduce Eisner to a new generation of readers? Most of his fans (like me) are Baby Boomers. And why wasn’t this posted under a “Will Eisner” tag?

Thanks for your comment, Carl. You know, I think a lot of folks of my generation (and I write this in my late 40s) got our first/best exposure to Eisner through his book, Comics & Sequential Art — and even only from there to A Contract With God! There were very few books about creating comics in those days (I’m thinking the early- to mid-80s) and Eisner’s always made the list. I think most of us were ill-equipped to really understand it at the time, having been first exposed to Stan Lee and John Buscema’s How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way. (The two books aren’t even trying to explain the same thing!) But Eisner’s book, I think, still stands as a good entry point, particularly because he references his own works throughout.

Of course, its tone is maybe a little too academic for casual readers, and it sort of assumes the reader has an interest in creating comics. The other thing, I think, is to get Eisner’s works on to reading lists, be they for classes, library programs, or just book clubs. I’ve seen Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home taught in college-level English. Why not A Contract With God — or for that matter, The Dreamer?

(Oh, and Eisner tag added!)