I was fascinated by the sections of Frederik L. Schodt’s Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics describing the breakneck, seemingly even harrowing nature of the Japanese manga business, and I wanted to learn more. I found what I was looking for in another book: Manga in Theory and Practice, by Hirohiko Araki.

I was fascinated by the sections of Frederik L. Schodt’s Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics describing the breakneck, seemingly even harrowing nature of the Japanese manga business, and I wanted to learn more. I found what I was looking for in another book: Manga in Theory and Practice, by Hirohiko Araki.

This slim volume from Shonen Jump was first published in English by Viz Media in 2017 – meaning some 20 years had passed since the revised edition of Schodt’s book. Still, not much seems to have changed in terms of how manga are produced.

It’s interesting to consider the title of Hirohiko’s English translation, even though it was surely chosen by its editors and publishers. For me, at least, it calls to mind Magick in Theory and Practice, one of the better-known books by the early 20th-century occultist Aleister Crowley. Crowley’s stated aim was to synthesize the aim of religion with the method of science. Araki’s philosophy, on the other hand, seems to be to synthesize the aim of art with the method of commerce – or is it the other way around?

A businessman’s take on art

Either way, the word “philosophy” is probably too strong. What Araki presents in his 226 pages is short on metaphysics and resembles a kind of operations manual for budding manga creators. It seeks to explain not just how to get published, but also how to craft what will most please editors and readers – always, always with the goal of producing the much-prized “big hit.”

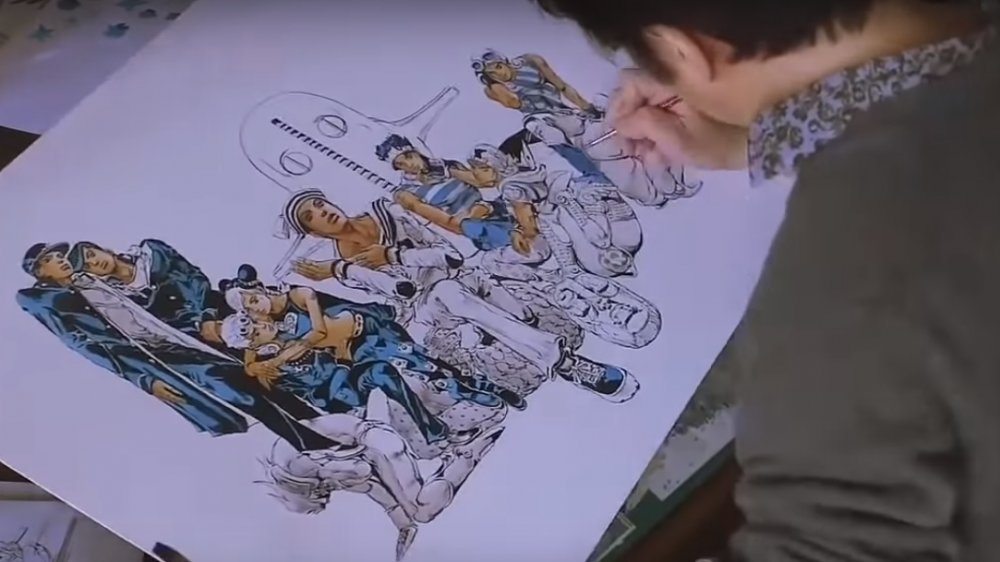

I must admit I haven’t been all that familiar with Araki’s work. The animated version of his epic, JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, is a mainstay of Western cable TV animation blocks and several online streaming services. While I’ve found it fairly entertaining, however, I’ve never read the manga, although clearly it has been wildly successful.

So here now is Araki, ready to tell you how he does it. And his trick, it seems, is to play the game that Schodt described years ago to the letter, and always with a laser focus on what’s likely to be a winner in the mass market.

He describes something he calls the “golden way” or “Royal Road” of manga. But this is no Zen-like journey along which each creator must find their own way. Rather, Araki claims to have found “the immutable rule of story writing,” with accompanying commandments covering everything from characters, to setting, to themes, to the “must-haves” of manga artwork.

Take, for example, Araki’s view of the hero’s journey. “Your protagonists must always be rising, rising, and rising still, building and building,” he explains. And in a familiar refrain, he adds, “or you won’t have a hit.”

Deadly sins of manga creation

Araki cautions that the process of crafting a big hit has many pitfalls. The wrong plot twist, he says, could be a “fatal, negative turn.” As he explains, “you want your readers’ state of mind to always remain positive.” Thus, while “you are allowed to start in a negative place and have the movement rise from there,” and temporary setbacks for the characters are allowed, the end result must always be a success story.

This strikes me as a characteristically Japanese attitude. Manga stories are nearly always about striving and struggling against adversity, with the characters ultimately achieving success. One story might be about a superhero battling monsters, while another might be about a sports team going to the big tournament, and another might be about the protagonist’s private struggle to become Japan’s best sushi chef. The struggle hardly seems important; it’s almost always about ending up being “the best” in the end.

But while Araki didn’t really invent the rules – he’s just written down his own take on them – the whole concept of “rules” in art is also a myopic approach that I occasionally find stifling as I encounter what I’d call cookie-cutter manga.

Consider, for example, the following Western works and characters, each of which commits at least one of Araki’s catalog of “fatal errors”:

- Marvel Comics characters, including Iron Man and Doctor Strange, often start out in a happy place, suffer a crippling setback, and then rise again (as opposed to constantly rising).

- The plot of the wildly popular movie Blade Runner could be described as a series of blunders: For a private eye, his investigation yields little, and the people he is seeking find him instead.

- The Godfather, although it depicts Michael Corleone’s rise as the leader of his family business, is also the story of a onetime war hero’s descent into crime, callousness, and moral turpitude.

- In Don Quixote, the author occasionally takes time out to speak to the reader, something for which Araki feels there can never be any excuse.

- In Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior, the titular character becomes a hero through the course of the story and achieves personal redemption, but he benefits in no other way, and by the end of the story he’s in the same place as where he started.

For each taboo that Araki offers up, there are innumerable counterexamples available in popular fiction, movies, TV, and comics. But this only drives home the point that Araki is not even trying to write a book about how to write an internationally bestselling novel. Rather, he wants to explain how he has been successful – and others might someday be similarly successful – in a business, a market, and an idiom that is uniquely Japanese.

Bedroom secrets of the manga stars

This brings us back to Schodt’s description of the Japanese manga business. Judging by Araki’s book, that world of long hours, toil and low pay still exists today, and Araki, while something of a superstar, seems all but resigned to it.

For example, in Araki’s world, every stage of manga creation must pass through the intermediary of an editor. That means everything from story ideas, to scripts, to sketchbooks, to layouts, to the eventual finished page are all subject to review and, potentially, rejection. Even ideas for manga series are dependent upon an editor’s approval. Araki describes how an editor once suggested he “do a manga that involved some kind of food” – which he dutifully did. (I doubt an X-Men writer ever fielded a similar request from Marvel.)

Japanese readers, too, have concerns and demands that may seem strange to Western readers. Araki writes of one of his “failures,” in which he used a real-life train station as a setting but populated it with anachronistic train cars. Readers, accustomed to meticulous attention to detail on such things, instantly noticed this “sham.” The result was that the manga lost readers, according to the Nielsen-ratings-like reader surveys that are administered every week.

That’s not good. Given the thoroughly commercial nature of the business, manga that isn’t objectively popular with readers isn’t paying the bills. A dip in popularity lasting more than a few weeks suggests the story isn’t worth a publisher’s time.

Taken with a grain of salt

But nothing mentioned here strikes Araki as strange or unusual. He works in a Japanese industry, for Japanese companies, for an audience that is first and foremost Japanese. He even admits that, although he travels regularly to gather photo reference for the exotic locales featured in JoJo, he “doesn’t handle non-Japanese food well.”

What this means is that if you’re a Western artist looking for advice on how to create manga that resembles some of the more popular titles that have been given English translation, Araki’s advice will be of limited utility. Unless you’re really aiming to be published in the Japanese market – which will necessarily mean drawing your panels from right to left, among other local conventions – you’d be better off understanding what local publishers offer and expect of you.

I’d also argue that Araki’s exceedingly narrow view of what constitutes a successful story is too limiting for the Western comics market. There are multiple Western publishers in business today whose editors are far more lenient than the publishers of workaday manga for the Japanese commuter crowd, and Western readers are much more eager for diverse storytelling.

If, on the other hand, you want a glimpse of how the sausage is made in the modern manga business in Japan, Manga in Theory and Practice gives you just that. By the end of the book, Araki admits that what he’s written is only his own opinion and that others might find it full of “misinformation.” Yet there’s no denying that Araki’s work has been commercially successful, both in Japan and internationally – so if you just want to know how it’s done, you could pick a worse example.

I wanted to create a one shot comic book but I it’s hard to differentiate between 100 words and the 1000 words because the story I’ll be covering will exceed a 100.