![]() Horror author H.P. Lovecraft never wrote with an Asian audience in mind. He identified as an Easterner, having spent most of his life in New England, but of the Far East he knew nothing. He never traveled abroad. In fact, the farthest he ever ventured from his beloved Providence was to New York, an experience that later led him to describe Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood as “a maze of hybrid squalor.”

Horror author H.P. Lovecraft never wrote with an Asian audience in mind. He identified as an Easterner, having spent most of his life in New England, but of the Far East he knew nothing. He never traveled abroad. In fact, the farthest he ever ventured from his beloved Providence was to New York, an experience that later led him to describe Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood as “a maze of hybrid squalor.”

About that word, “hybrid.” Lovecraft wasn’t one for mixing with foreigners. While the degree to which he was an overt racist is sometimes overstated, his xenophobia and his mistrust of unfamiliar cultures were real. In fact, they underlie many of his most memorable stories.

Given all of this, it may be surprising to learn that, in my opinion, some of the best recent comics adaptations of Lovecraft’s weird fiction have come from the pen of Japanese manga artist Gou Tanabe.

Lousy Lovecraft

How can this be? Tanabe’s culture and the one that produced Lovecraft couldn’t be more different. But then, quality interpretations of Lovecraft’s writing for other media are rare, and American attempts are no exception.

The problem with many Lovecraft adaptations is twofold. First, they tend to emphasize bizarre and fantastic imagery, shocks, and gore. Second, they flesh out the characters, giving them backstories, unique characteristics, and natural dialogue.

For modern horror, these might be laudable traits. But Lovecraft simply wasn’t modern, even by the standards of the early 20th century. He favored obscure words and archaic spellings. His dense prose, occasionally bordering on logorrhea, is often ridiculed today. And his characters are seldom more than stand-ins for the author, with all his bookish quirks intact. When an adaptation loses any of this, it loses what makes Lovecraft’s writing unique and memorable.

Perhaps even worse are the pastiches of Lovecraft’s style by other authors, including contemporaneous ones and works produced in later years. Too many of them fall back on the worn-out concept of a war between good and evil, an idea with which Lovecraft himself had no truck.

A few Lovecraft comics from the U.S. and Europe get it right. Arguably, no film ever has. That’s what makes what Gou Tanabe has accomplished so impressive.

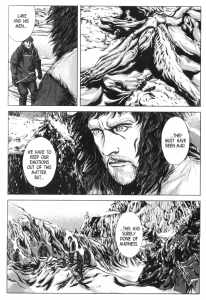

Tanabe’s approach

First, although most manga never leave Japanese shores, Tanabe makes no concessions to that fact. He doesn’t try to transpose Lovecraft’s characters or settings into Japanese ones. He sticks to what’s in the text and plays everything straight, right down to the source material’s stilted dialogue and period trappings.

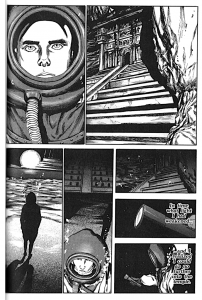

Nor does he use any of the visual tropes that Western readers have come to associate with manga. There are no giant eyes, spiky hairstyles, exaggerated poses, or speed lines everywhere. Instead, he adopts a style that’s close to magazine illustration, with subtle cartooning elements that don’t distract from Lovecraft’s tone.

Also notable is Tanabe’s use of narrative text. Most manga never use it, sticking to speech balloons and sound effects exclusively. But Tanabe doesn’t shy away from narration when it’s the best way to convey Lovecraft’s characters’ internal monologues.

Whether Tanabe had an international audience in mind when he began his adaptations, I can’t say.

Deep cuts

Looking at the list of stories he has adapted, you can tell Tanabe has a genuine appreciation of Lovecraft. His choices are not always obvious ones. Some are shorter tales, which is a natural way to go when an artist is budgeting time for the number of drawings it will take to adapt a prose story. But length can’t be the only factor in his decisions.

For example, one selection is “The Temple,” a personal favorite of mine. It’s the tale of a German U-boat commander whose ship meets its end amid strange goings-on beneath the sea. It’s a curious story, because contrary to modern views on Lovecraft’s own character, it portrays the protagonist’s racism and nationalism as his downfall. Also, while the story predates World War II, it’s an interesting choice for a Japanese artist to adapt, given Japan’s later involvement in that war and with Nazi Germany.

For example, one selection is “The Temple,” a personal favorite of mine. It’s the tale of a German U-boat commander whose ship meets its end amid strange goings-on beneath the sea. It’s a curious story, because contrary to modern views on Lovecraft’s own character, it portrays the protagonist’s racism and nationalism as his downfall. Also, while the story predates World War II, it’s an interesting choice for a Japanese artist to adapt, given Japan’s later involvement in that war and with Nazi Germany.

Another story Tanabe adapts is “At the Mountains of Madness.” That might sound like no-brainer to the Lovecraft fan cult, but in truth it’s an ambitious choice. The original novella is dense with text and it’s short on action. Adapting it to a visual medium, and especially comics, takes real dedication, and Tanabe does a fine job of it.

Some quibbles

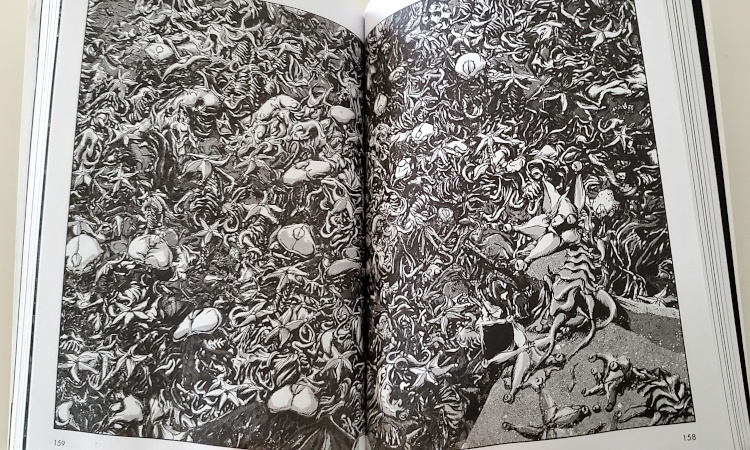

Of course, not all is perfect. While Tanabe’s highly realistic style is nice to look at, it can also be hard to parse. He makes extensive use of gray tones to add form and depth, but this can also render panels murky and indistinct, particularly in dark scenes. His dot patters, most likely applied digitally, lack the nuance of hand-drawn effects, for example in the engravings of Gustave Doré.

This becomes a real problem in silent sequences. For example, we might see a character’s frightened face in a reaction shot but are then forced to linger on other panels to figure out what shocked him.

Also, because Tanabe’s narrative text lacks boxes or balloons behind it, it can be hard to read against the artwork. Again, the worst examples are dark panels, where text is printed in black with a thick white outline.

Also, because Tanabe’s narrative text lacks boxes or balloons behind it, it can be hard to read against the artwork. Again, the worst examples are dark panels, where text is printed in black with a thick white outline.

Much of the blame for this must fall on Tanabe’s publisher. Reproducing his art at traditional Japanese tankobon size – not much larger than a pocket paperback, and about half the size of an American comic book – does it no favors. It’s unclear whether this was the decision of Dark Horse Comics, Tanabe’s U.S. publisher, or if it was mandated by whomever controls distribution of his work internationally.

More to come?

Production issues aside, Gou Tanabe is a creator whose work deserves attention from anyone who enjoys Lovecraft, manga, or comics in general. Dark Horse has published three English-language editions of Tanabe’s Lovecraft manga to date, including The Hound and Other Stories and a two-volume adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness.

Other, European publishers have released these same books in local translations, in addition to further volumes that have yet to be published in the United States (despite having similar cover designs to the Dark Horse editions). With luck, sales of Dark Horse’s first three volumes will be enough to convince it to continue the series.

Better still, however, would be for Dark Horse to collect these Lovecraft adaptations in a deluxe hardcover edition that reproduces the art at its original size, as it has done for Berserk, Blade of the Immortal, and Hellsing. The quality of the work deserves it.